-40%

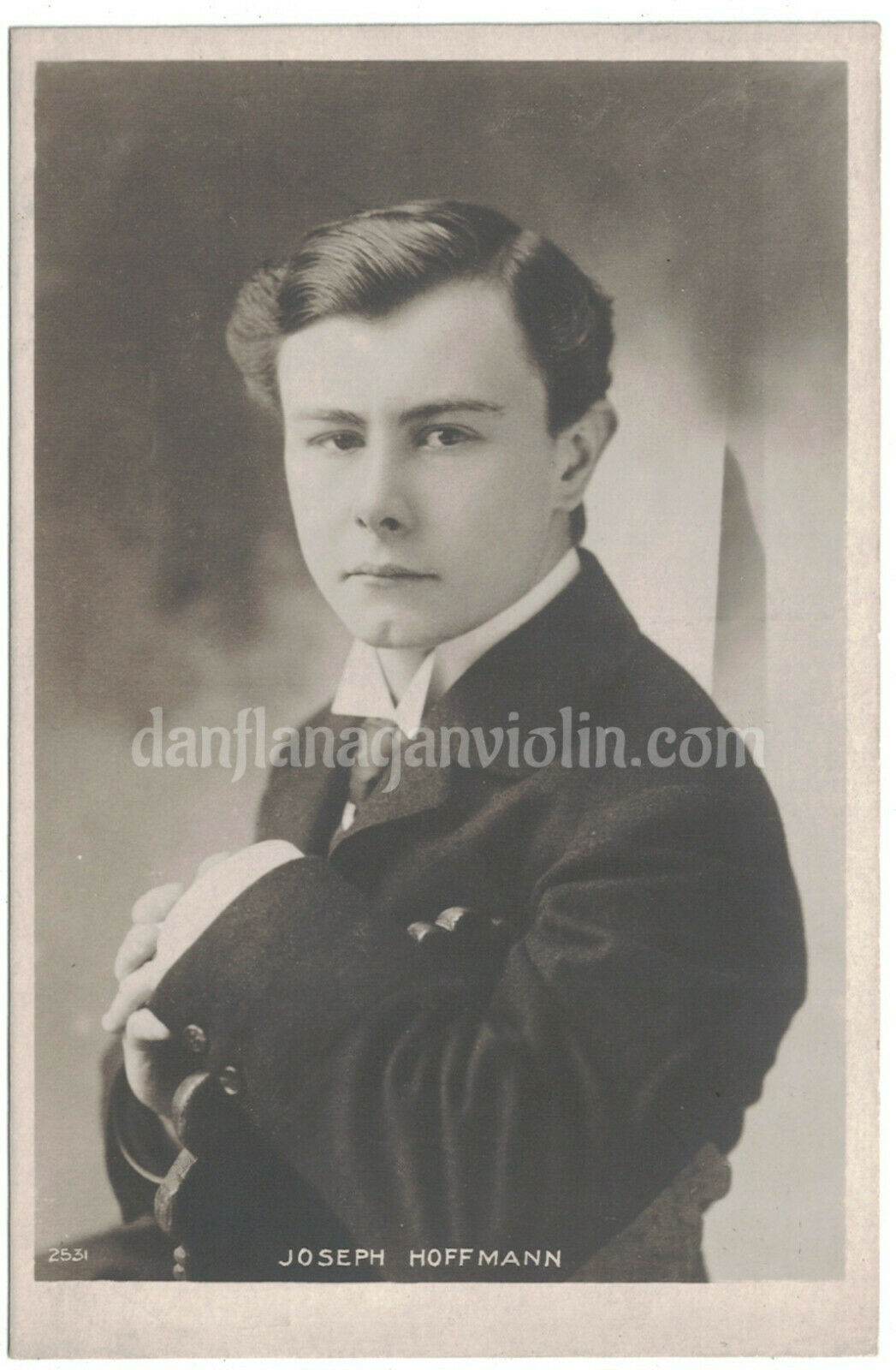

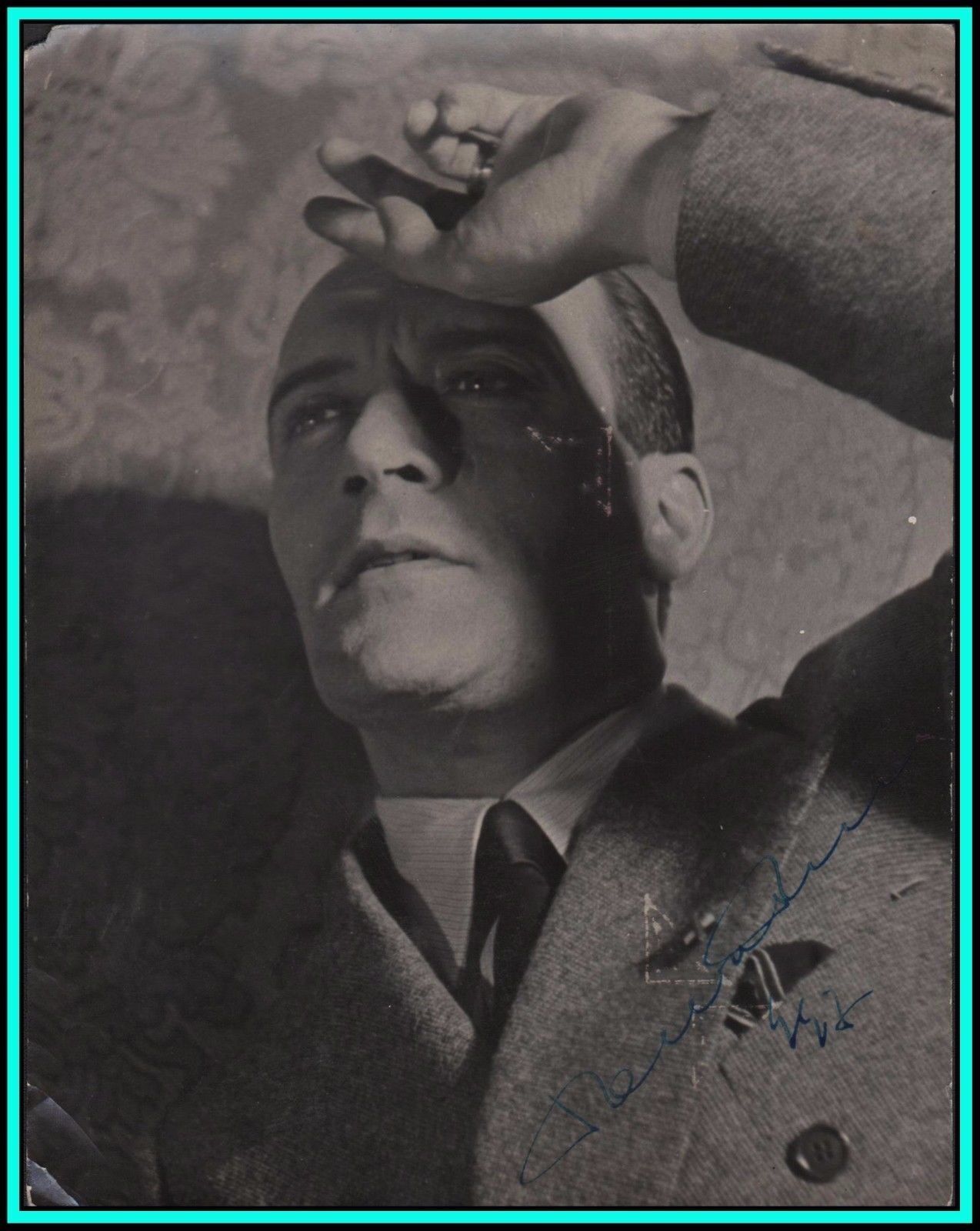

Josef Hofmann photo piano pianist Joseph Hoffmann

$ 52.79

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Hello!For sale I have a period postcard photo of pianist Josef Hoffmann. A handsome pose from the young man, likely from Sarony in New York. Printed in England. Unused. Excellent condition. 3.5 x 5.5 inches. USPS Priority Mail insured.

I have been a professional violinist for 20 years. I currently teach violin at University of California, Berkeley, and play Concertmaster for the Sacramento Philharmonic and Opera. I've been buying and selling music memorabilia on eBay since it was invented and I've been buying antique art from European and American auction houses for a decade. All pieces for sale are guaranteed authentic and come from my personal collection, which numbers in the thousands. To learn more about me visit www.danflanaganviolin.com.

Josef Casimir Hofmann

(originally

Józef Kazimierz Hofmann

; January 20, 1876 – February 16, 1957) was a

Polish American

pianist,

composer

, music teacher, and

inventor

.

Josef Hofmann was born in

Podgórze

(a district of

Kraków

), in

Austro-Hungarian

Galicia

(present-day

Poland

) in 1876. His father was the composer,

conductor

and pianist Kazimierz Hofmann, and his mother the singer Matylda Pindelska. He had also an older sister - Zofia Wanda, b. June 11, 1874 also in Krakow. Throughout their childhood, their father, Kazimierz, was married to Aniela Teofila

née

Kwiecińska (born on January 3, 1843 in

Warszawa

),

[2]

who, after moving to Warsaw in 1878 with her husband, died there on October 12, 1885,

[3]

entry 1392. Then the next year Kazimierz Mikołaj Hofmann married on June 17, 1886, Matylda Franciszka Pindelska - the mother of his children, (daughter of Wincenty and Eleonora

née

Wyszkowska, b. in 1851 in Kraków) in the Holy Cross Basilica in Warszawa.

[4]

In order to ensure their son Josef a thorough musical education, the whole family moved to Berlin from 1886. Josef Hofmann, a child prodigy, gave a debut recital in Warsaw at the age of 5, and a long series of concerts throughout Europe and Scandinavia, culminating in a series of concerts in America in 1887-88 that elicited comparisons with the young

Mozart

and the young

Mendelssohn

.

[5]

Anton Rubinstein

took Hofmann as his only private student in 1892 and arranged the debut of his pupil in Hamburg, Germany in 1894. Hofmann toured and performed extensively over the next 50 years as one of the most celebrated pianists of the era.

[6]

In 1913, he was presented with a set of keys to the city of

St. Petersburg

, Russia.

As a composer, Hofmann published over one hundred works, many of those under the pseudonym

Michel Dvorsky

, including two

piano concertos

and

ballet music

. He made the

United States

his base during

World War I

and became a US citizen in 1926. In 1924, he became the first head of the piano department at the inception of the

Curtis Institute of Music

, Philadelphia, and became the Institute's director in 1927 and remained so until 1938.

He was instrumental in recruiting illustrious musicians such as

Efrem Zimbalist

,

Fritz Reiner

,

Marcella Sembrich

, and

Leopold Auer

as Curtis faculty. Hofmann's pupils included Jean Behrend,

Abram Chasins

,

Abbey Simon

,

Shura Cherkassky

,

Ezra Rachlin

, Nadia Reisenberg (see

[7]

), and Harry Kaufman. While not a pupil,

Jorge Bolet

benefited from Hofmann's interest. In 1937, the 50th anniversary of his New York debut performance was celebrated with gala performances including a "Golden Jubilee" recital at the

Metropolitan Opera

,

New York City

. In 1938 he was forced to leave the Curtis Institute of Music over financial and administrative disputes. In the years from 1939 to 1946, his artistic eminence deteriorated, in part due to family difficulties and alcoholism.

[8]

In 1946, he gave his last recital at

Carnegie Hall

, home to his 151 appearances, and retired to private life in 1948. He spent his last decade in

Los Angeles

in relative obscurity, working on inventions and keeping a steady correspondence with associates.

[9]

As an inventor, Hofmann had over 70 patents, and his invention of pneumatic shock absorbers for cars and airplanes was commercially successful from 1905 to 1928. Other inventions included a

windscreen wiper

, a furnace that burned crude oil, a house that revolved with the sun, a device to record dynamics (U.S. patent number 1614984

[10]

) in reproducing

piano rolls

that he perfected just as the roll companies went out of business, and piano action improvements adopted by the Steinway Company (U.S. patent number 2263088

[11]

).

He moved to Los Angeles in 1939. Hofmann died of

pneumonia

on February 16, 1957 at a nursing home in

Los Angeles, California

.

[1]

He had four children. In 1928, he revealed that he and his first wife, Marie Eustis, had divorced in 1924; he also revealed that he had remarried, to Betty Short.

[12]

[13]

The Josef Hofmann Piano Competition, co-sponsored by the American Council for Polish Culture and the University of South Carolina Aiken was established in his honor in 1994.

[14]

Anton Rubinstein

heard the seven-year-old Hofmann play Beethoven's

C minor Piano Concerto

in

Warsaw

and declared him to be an unprecedented talent.

[15]

[16]

At Rubinstein's suggestion, German impresario Hermann Wolff offered career management and offered to send the boy on a European tour, but Hofmann's father refused to let the boy travel until he was nine years old. At that age, Hofmann gave concerts in Germany, France, Holland, Norway, Denmark, Sweden, and Great Britain.

[15]

At the age of 12, young Josef Hofmann was probably the first pianist of note to record on Edison's

phonograph

;

Hans von Bülow

recorded a

Chopin Mazurka

on Edison's improved phonograph the same year, i.e., 1888.

[17]

In 1887, an American tour was arranged, with three months of performances that included fifty recitals, seventeen of which were at the

Metropolitan Opera House

. Yet soon after, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children stepped in, citing the boy's fragile health. However, as per the contract that had paid Hofmann ,000, he was legally obliged to complete the tour. The contract was rendered void by

Alfred Corning Clark

who donated ,000 and, in turn, legally forbade Hofmann to perform in public until he turned 18 years old.

[6]

The final segment of the tour was cancelled and the family returned to Potsdam, outside Berlin. This marked the end of Hofmann's child prodigy years. (See

[18]

and

[15]

for details.)

Clark's donation enabled Hofmann to continue individual study in science and mathematics, and he continued to take music lessons from

Heinrich Urban

(composition) and with the pianist and composer

Moritz Moszkowski

. In 1892, Rubinstein accepted Hofmann as his only private pupil, the two meeting for 42 sessions in Dresden's Hotel d'Europe. Initial lessons, a week apart, included ten

Bach

Preludes and Fugues and two

Beethoven

sonatas, from memory. Hofmann was never allowed to bring the same composition twice, as Rubinstein said as a teacher he would probably forget what he told the student during the previous lesson. Rubinstein never played for Hofmann, but gave ample evidence of his pianistic outlook during many recitals the boy heard. In a three-day period Hofmann heard in Berlin's new Bechstein Hall recitals by

Hans von Bülow

,

Johannes Brahms

and Rubinstein, and commented on their radically different playing. Rubinstein arranged Hofmann's adult debut on March 14, 1894, in Hamburg's Symphonic Assembly Hall, the piece being Rubinstein's

Piano Concerto No. 4 in D minor

, with the composer conducting. After the concert, Rubinstein told Hofmann there would be no more lessons, and they never saw each other again. Rubinstein returned to Russia and died later that year. In later years Hofmann referred to his relationship with the titanic Russian master as the "most important event in my life.".

[15]

By the early 1930s, Hofmann had become an alcoholic but he retained exceptional pianistic command throughout this decade;

Rudolf Serkin

and a young

Glenn Gould

have recounted magical impressions created on them by Hofmann's concerts in mid-and-late 1930s.

[19]

After his departure from the Curtis Institute in 1938, a combination of his drinking, marital problems and a loss of interest in performing caused a rapid deterioration in his artistic abilities. Commenting on Hofmann's sharp decline,

Sergei Rachmaninoff

said, "Hofmann is still sky high ... the greatest pianist alive

if

he is sober and in form. Otherwise, it is impossible to recognize the Hofmann of old".

[20]

Oscar Levant

wrote, "one of the terrible tragedies of music was the disintegration of Josef Hofmann as an artist. In his latter days, he became an alcoholic. …[H]is last public concert … was an ordeal for all of us".

[21]

Harold C. Schonberg

has argued that Hofmann was the most flawless and possibly the greatest pianist of the 20th century.

[6]

HMV and RCA unsuccessfully pursued recording projects with Hofmann in the 1930s.

Rachmaninoff

dedicated his

Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor

(1909) to Hofmann, although Hofmann disliked it and never played it. Older generation critics such as

James Huneker

labeled Hofmann the "king of pianists", and Samuel Chotzinoff called him the "greatest pianist of our time." Contemporaries such as

Rachmaninoff

, Ignaz Friedman, Josef Lhévinne, and Godowsky considered Hofmann to be, overall, the greatest pianist of their generation,

[20]

[24]

but the acclaim was not so universal from the next generation of pianists.

[29]

In his autobiography

Arthur Rubinstein

criticized Hofmann as someone who took interest in only the mechanics of music and not in its heart or spirituality, and commented that at the end of Hofmann's career "he was left with nothing after his technique left him".

[30]

Claudio Arrau

dismissed Hofmann (along with

Paderewski

) as someone who only happened to be very famous and said "I didn't know what to do with him".

[31]

Sviatoslav Richter

, after listening to a Hofmann RCA test pressing of the Scherzo from Beethoven's Sonata in E-flat, Op. 31, No. 3, considered the older pianist to be technically "stunning", but noted that Hofmann ignored the composer's

sforzando

markings; while

György Sándor

has called him the greatest of all 20th-century pianists in terms of music, interpretation, and technique.

[32]

Hofmann's own student

Shura Cherkassky

compared Horowitz favorably with Hofmann as follows: "Hofmann was possibly the greater musical mind. But, I think, Horowitz was the greater pianist, the greater virtuoso—he somehow appealed to the whole world. Hofmann could not communicate on that level".

[29]

To balance the record,

Earl Wild

acknowledged Hofmann’s style as the biggest influence on him gaining a fluid and flexible technique: ‘His interpretations were always delivered with great logic and beauty.’

Jorge Bolet

is reported to have said that whenever he heard either Rachmaninoff or Hofmann, he always thought to himself, ‘Every note that they play – that is what I would like to play.’